Left or Right Side? Self-understanding vs Self-deception: An introduction to the “Conscience Chart,” Part I.

[Reading Time: 14 minutes

Note: Part of this was published in the series, What is the Riddle of the Sphinx, Part I & Part II]

Introduction

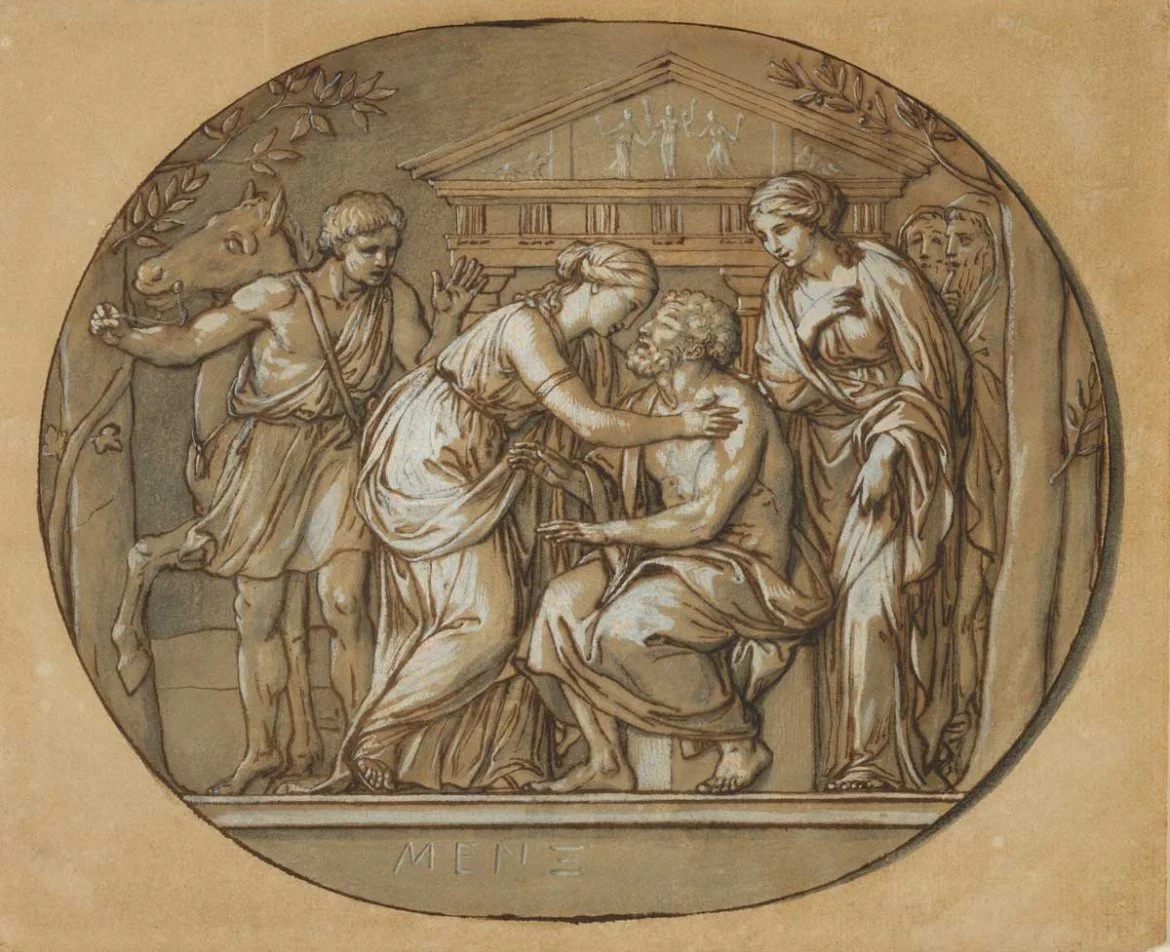

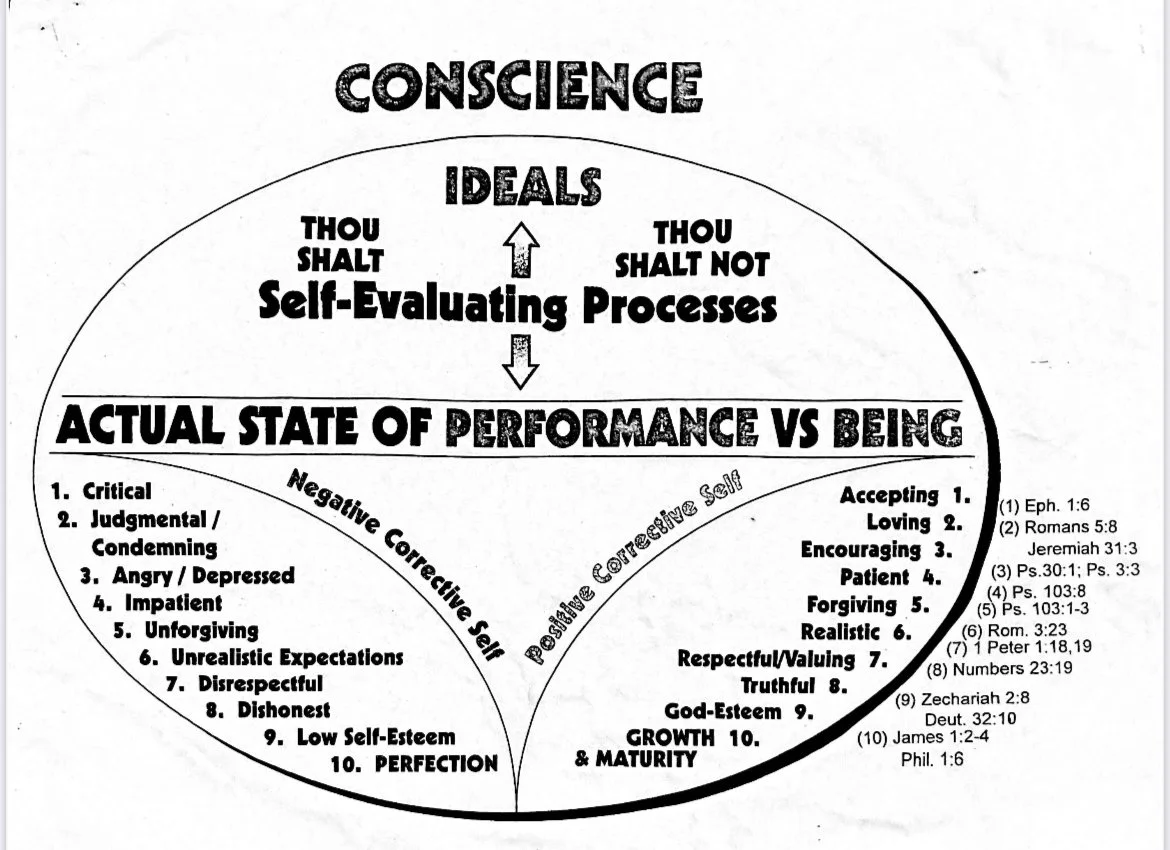

In another writing, we began an examination into the critical importance of self-knowledge vs self-deception. And there we introduced what has come to be known as the “Conscience Chart,” a graphic (below) that helps us differentiate in real-time what is actually driving our behavior.

Are we living in a world of ideals where we are the subject of every verb; where we are the ones who must perform so as to ensure a given outcome (be it at home or with our children or at work or in our finances or with any number of our ever-increasing short- or long-term goals)?

Or is God the subject of every verb?

Which is to say,

Is He the One Who is leading us, directing us, guiding us?

Or is it ourselves?

Is He the One Who accepts us, loves us, forgives us?

Or is all this dependent upon us?

Is He the One Who encourages us, comforts us (confortare), strengthens us, teaches us Truth, opens our eyes to those things that we need to confront?

Or does all this come through our spiritual performance?

Because we prayed enough, fasted enough, repented enough, read enough Scripture, led enough Bible studies, led enough small groups, volunteered enough, gave away enough, did enough short-term missions, etc., etc., etc.?

Is He the One Who knows us and accepts us, values us—eternally—in a way that is not finally dependent on our ever-changing level of performance?

Is He the One Who reacts to our volatility with calmness and patience?

Is He the One Who, when he make mistake after mistake after mistake, responds with infinite mercy and an indelible grace that is inexhaustible?

And when we start to ask these questions, we can then relate our answers to the real-time emotions that we begin feeling.

Are we being critical, judgmental, condemning?

Could this mean that we are operating on the “left side” (see above).

Are we angry and depressed?

Is this flowing out of unrealistic expectations we have of ourselves or others?

Could we be burdened by an ever-increasing weight of all life’s expectations?

Because we are living in a world of ideals (This is the way it should be…and if not…) and not reality (This is actually the we it is).

And are we inpatient and unforgiving?

And is this because cannot let go of our anger and resentments due to the fact that we have not yet experienced the breadth of God’s patience with us nor received His grace in forgiveness?

All this to say very simply,

Are our lives dependent on what we achieve?

Or on what we receive?

And with this introduction to the Conscience Chart, we move into an absolutely fascinating Greek tragic drama, Oedipus Rex, which we might have read way back in high school…but which offers us today a living picture of where self-deception can lead us…

Self-knowledge: An ancient philosophical perspective

Offering one final introductory remark, we should remember that the Ancients well understood that true knowledge begins with accurate self-knowledge. To the degree that the words inscribed over the Oracle at Delphi were

“Know Thyself” (gnōthi seauton)

And while the original meaning of the phrase likely communicated the idea of “knowing your limits,” Socrates and his philosophical heirs came to see it in more comprehensive terms.

His student, Xenophon (c. 430–354 BC), presents a conversation between Socrates and a highly educated and ambitious young man (Euthydemus). Seeing his potential yet understanding that his overconfidence could prove disastrous when he enters into the realm of politics, the old philosopher pursues the below line of questioning:

“Then did you notice somewhere on the temple the inscription ‘Know thyself'?”

“I did.”

“And did you pay no heed to the inscription?

Or did you attend to it and try to consider who you were?”

“Indeed I can safely say that I did not; because I felt sure that I knew that already;

for I could hardly know anything else if I did not even know myself”

(Xenophon, Memorabilia, 4.2.24-25).

In this short excerpt, we see that even with all his brazen confidence Euthydemus nevertheless admits that if he does not know himself…then he can’t really know anything else. And with this admission of the critical importance of self-knowledge as a starting point, Socrates then guides him into greater understanding.

(And though we won’t examine them here, we could highlight this theme in further dialogues of another of Socrates’ more famous student, Plato, ranging from the Phaedrus, 229e-230a to the Apology, 21d-22a to Protagoras, 343b, etc., etc.)

Moving forward, however, in this conversation with Euthydemus, Socrates next warns of the great evil that comes from self-deception.

From self-knowledge to self-deception

Here in the form of questions, Socrates makes two clear points:

“Is it not clear too that through self-knowledge men come to much good?

And through self-deception (epseusthai: The middle voice of pseudō: ‘lying to oneself’ and ‘being in a state of falsehood’) men come to the greatest of evils?’ (pleista kaka, 4.2.26).

That is to say, if we don’t know who we are and live in a state of self-delusion with endless, unrealistic expectations, great harm will inevitably engulf us.

Yet Socrates goes further, next revealing that the layers of our self-deception radiate outwards, affecting not only ourselves, but also our view of others, our work and even all our affairs:

“Those who do not know and are deceived in their estimate of their own powers, are similarly disposed toward other people and other human affairs.

They know neither what they need,

nor what they are doing,

nor those with whom they converse;

but being wholly mistaken (diamartanō: an intensification [diá] of the Greek NT verb most often used for ‘sin’ and ‘error’ [hamartánō]) in all these respects,

they fail to come to the good and stumble into many evils” (4.2.27).

That is to say, our false or deceived judgements about ourselves become like a virus that infects everything it touches.

And the final result is our being led “into many evils.”

A great warning.

But one that underlies much of the Greek tragic literature...and, as we’ll see in Oedipus Rex, the very means by which the Sphinx takes control, the Hydra poisons us and Cerberus bites, scrapes and claws at us, so as to keep us from seeing the things necessary for our healing.

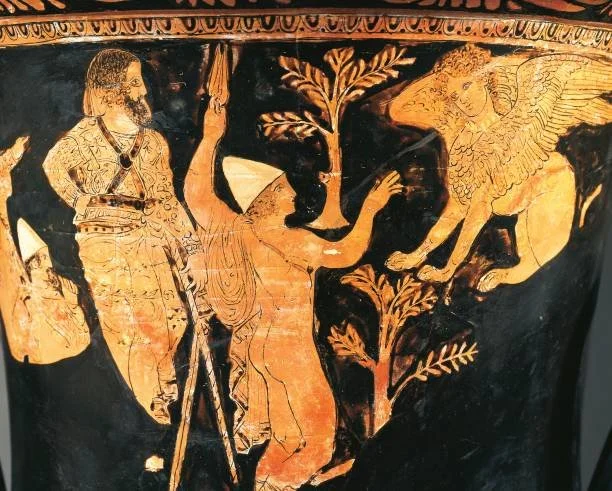

Oedipus Rex: Who is the Sphinx?

Moving, then, from philosophy into the realm of tragic drama, we now direct our attention to the extraordinary trilogy of Oedipus Rex, where these questions of self-knowledge vs self-deception become embodied.

As the story unfolds, we begin to see that the narrative engine of the play is not the intersecting plotlines of murder, disease, plague and political intrigue.

Everything hinges upon one thing: self-knowledge vs self-deception.

If the family secrets are brought into the light and confronted, there is the possibility of healing. If not, only tragedy awaits.

The play opens after Oedipus has just solved the Sphinx’s riddle and has been declared the "Savior of Thebes."

Savior and yet, if he does not confront his past, Destroyer…

But who was the Sphinx?

The Sphinx was an absolutely brutal creature. Herself the daughter of Typhon (the Storm-giant) and Echidna (the "Mother of All Monsters"), she was the literal offspring of chaos and violence. Yet rather than confront this horrifying reality of her own family lineage (or, we might say in more modern psychological terms, her “family system”), she suppresses it deep within herself in ways that progressively distort her femininity into monstrous proportions.

And how does the monster become manifest?

Though she still retains identifying features of a female with a woman’s head and breasts, her body becomes that of a lion (the “king of the jungle,” so to speak). Yet even more fascinating, from her lion’s body protrude wings for fight…as in to say, she pursues you wherever you go. And finally, as for her extremities they are the claws of very particular bird of prey—a vulture.

Not an eagle; not a falcon; a vulture, meaning that she does not pursue and kill the prey herself; she only arrives to claim what has already died (“For you have died…”). And when she does, she then devours the person whole…one by one.

The “Devouring Mother”

Viewed as the archetype of the “Devouring Mother,” she dominates her offspring through unremitting control (C. G. Jung, Symbols of Transformation in CW 5, §§260–270). And though she, in one sense nurtures her children, she ultimately dominates them, threatening at every moment to swallow their ego whole.

Her image, we might say, is the personification of a “mommy wound.”

And to apply it to our modern context, we could say that she is the overbearing ‘soccer’ or ‘homeschool mom’, who keeps children under her tight control in a way that prevents any genuine development outside of her dominance.

She takes her seat, as it were, over the mount of her family’s home, controlling the household through continual riddles...to which only she knows the answer. And ruling through this overweening psychological control, she keeps her family system under her mastery.

But that is not all, looking beyond her decent and lineage, we ask further,

Who was her sister?

And who was her brother?

The Hydra

Her sister, we discover, was the Hydra, the multi-headed serpent of proliferating trauma. Cut off one head and two more grow up in its place.

As in to say, fail to address the root cause and more pathologies emerge.

If we have sudden chest pain or worsening back pain or new vertigo or a wave of panic attacks or unremitting insomnia…and if our provider simply orders labs or imaging and prescribes medications, the symptoms may temporarily improve but two more worse pathologies may grow up in its place.

That is to say, when we treat Hydra’s new heads, the result is that more heads keep on emerging. Back pain becomes stomach pain becomes headaches becomes dizziness become fatigue becomes anxiety and depression.

And if our physician keeps ordering more tests or referring us to more specialist, we become like the woman with the “issue of blood,” who

“suffered many things from many physicians” and

“spent all that she had” but is

“no better, but rather growing worse” (Mk 5:26).

But that’s only the Sphinx’s sister, Hydra.

What about her brother?

From Hydra to Cerberus: The deepening layers of the unconscious

Going still further, the brother of the Sphinx was Cerberus, the three-headed dog that guarded the Underworld. The vicious guardian, we might say, of our personal, familial and cultural, unconscious worlds…who ‘barks’ and ‘bites back’ whenever we get too close to the truths we have so effectively buried (our personal unconscious).

Or our family has generationally suppressed (the generational unconscious).

Or our culture has blocked out of sight (the collective unconscious).

And upon such a city blinded and collectively held captive by what is staring them in the face…but they refuse to confront, the Sphinx finally descends.

The Sphinx, the “Devouring Mother,” that “cruel singer” (line 42), who traps her “children" (the developing ego), lulling them into a state of lifelong dependency and intellectual paralysis before she ultimately swallows them whole.

And so, the city of Thebes, blind to what actually threatens them most, believes they have been truly set free when Oedipus overcomes the Sphinx.

But is this really the case?

The riddle of the Sphinx

The Sphinx, we learn, had been sent to Thebes by the gods as a punishment for the crimes of the previous King Laius. Setting herself upon Mount Phikion, she ruled over the city through physical and psychological terror.

Demanding a deadly “toll” for passage, she spoke a riddle to every passerby. If they solved it, they could pass through unharmed. If they failed, they would be strangled (the word, sphingein, from which her name is derived, means to ‘strangle’) and then consumed alive (as it were, being already dead).

This sort of psychological oppression was incredibly unique because it gave the victim a false sense of agency. That is to say, they had the "opportunity" to save themselves through their intellectual powers, yet lacked the wisdom to do so. This is a critically important dimension of the play and will serve only to heighten its dramatic irony—intellect without truth will bring total blindness.

The Sphinx, however, before the start of the play’s drama, had been overcome by the mysterious newcomer, Oedipus, who, for his answer to her famous riddle, had ascended to the royal throne.

Her riddle:

“What goes on four legs in the morning,

on two legs at noon,

and on three legs in the evening?”

His answer:

“Man.”

Who as a baby in the “morning” of life crawls on four limbs;

as an adult at “noon” walks on two legs;

and as an old man in the “evening” of life, walks with a cane, a third leg.

And what happens when Oedipus solves the riddle that no one else before him had been able to answer?

Victory at one level; Defeat at another

Oedipus’ boldness in first standing up to the Sphinx and then answering her riddles with all the powers of his intellect brings him and the city of Thebes immediate victory.

The Sphinx, in a rather sudden, unexpected way, immediately “casts herself down from the citadel” in defeat (Apollodorus, Library, 3.5.8). No epic struggle; no violent clash. In fact, there is no resistance at all. Oedipus speaks the word and she “throws herself into the sea” to her death (Hyginus, Fabulae, 67).

The question, then, is why?

The power of his conscious-level intellect has overcome the “Devouring Mother,” freeing the city from her terrorizing control. The domination she exerted over Thebes through her unsolved riddles has finally been broken.

But—and this is the key—once she is gone, a much deadlier disease awaits…which is buried far below the surface in the dark layers of the unconscious.

Some commentators have even asserted that the Sphinx’s act of casting herself down to her death is but a stratagem to draw Oedipus into an even darker deception. That is to say, by her dramatic suicide she is enabled to secure a greater victory.

What??

How is that in any way possible?

The real battle begins

Though Oedipus has solved the puzzle in an abstract manner (“It is man”), he has failed to recognize himself in the story (“It is me”) as well as his family (“It is my father and mother”) since ancient sources held that the crimes committed by the royal house (his own house) were the reason for the scourge of the Sphinx.

And while Oedipus, through the light of his intellect, has overcome the enslaving power of this mythical beast, his victory over her will become the very means by which he will himself be blinded and then bound to a different mother—his own.

That is to say, her suicide embodies a failed initiation of the hero into manhood, the consequence of which will prove catastrophic, not merely to Oedipus, but also to the realm over which he now rules.

And this may be a reason why Sophocles seems to make such a point of the fanfare and hero worship of Oedipus by the populous after his initial victory:

“You came to Thebes and cut us loose from the bloody tribute we had paid that harsh, brutal singer (35-36).

“We taught you nothing, no skill, no extra knowledge, still you triumphed” (37).

“You gave us back our lives” (39).

“You are the mightiest head among us” (49).

“You are our life’s establisher” (57).

The first threat has been defeated…yet through his conscious-level, intellectual victory Oedipus has been lifted up into a blinding hubris that will keep him from actually seeing what is the true menace to the city.

From the Sphinx to the Plague: Our next question

Going still further, with the Sphinx now overcome, a new threat appears as a “deadly pestilence,” whose effects are far, far worse.

For this new disease is not terrorizing the inhabitants one by one, but destroying the city’s land and cattle, making “pregnant women lose their children” and filling “black Hades” with “groans and howls” as the “fiery god” strikes them down (22-31).

That is to say, whereas the Sphinx was an individual threat operating at the conscious-level through her riddles, the Plague is giving rise to darker, unconscious threats, suppressed for years and years, but now bubbling up from below the surface (Cerberus).

And whereas the Sphinx had been cast out, something far worse has now grown up in its place (Hyrdra).

All of this because the core issues have not been dealt with.

Oedipus has overcome a mythically terrifying beast; yet her siblings are still very much alive, ravishing the population through a pandemic.

And here, we might ask the question whether this infection, this “polluting stain” is not that “universal, hereditary sickness" …that “horrible, deep, inexpressible corruption” identified as…nothing other than…sin (Formula of Concord, Article I)?

A malady which does not distinguish between man, woman or child;

A disease that infects every person whom it touches;

A “deadly pestilence” that continues replicating and spreading until it has destroyed absolutely everyone and everything.

Conclusion: From “inexpressible corruption” to ineffable grace

Drawing this opening piece to a conclusion, we commenced with the theme of self-knowledge vs self-deception. And beginning with Greek Philosophy, we next moved into the realm of Greek Tragedy, where this philosophical understanding, so to speak, took on flesh and blood.

And there in Sophocles’ drama of Oedipus Rex, we encountered much more than a mere ancient literary tale; we discovered depths of psychological insight into the riddle not only of who we are as human persons, but moreover, how blind we actually are to our own histories…and how blind we are to who our family is…and how blind blind to what our culture is…and, finally, how blind we are to what threatens to destroy all of them.

And at this point, the riddle of the Sphinx advances beyond the domain of a mere intellectual enigma which can be solved through our conscious-level mind. Our brilliance avails us nothing here.

What is needed is honesty and courage.

Because what will be unleashed out of the unconscious worlds of Cerberus, our cerebral minds cannot handle. For when the Sphinx is intellectually overcome what remains beneath the surface is a much more “deadly pestilence.”

And it is into this all-encompassing pandemic which we will look in our next writing, which will require depths of ineffable grace.

To which we say in preparation,

Kyrie eleison!