The Timeless Tense, Part I. The Aorist (A + Horízō) in the Incarnation: The fullness of eternity piercing the “horizons” of time

[Reading Time: 15 minutes]

“And the Word became flesh (sárx egeneto)

and dwelt (lit. tabernacled: eskēnōsen) among us”

καὶ ὁ λόγος σὰρξ ἐγένετο

καὶ ἐσκήνωσεν ἐν ἡμῖν

John 1:14

Introduction:

A language echoing the between the Dimensions

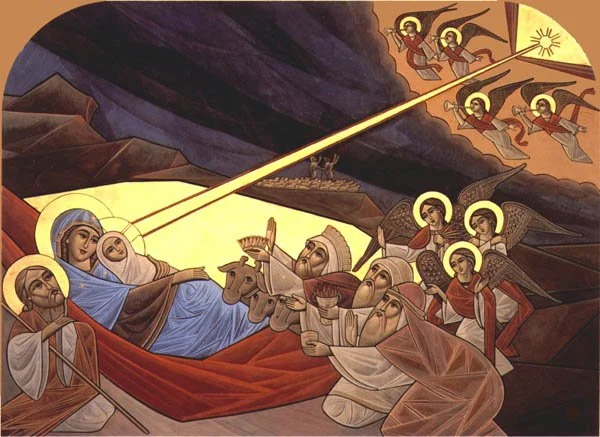

Time pierced through with timelessness; the Third Dimension interpenetrated with the Fourth; Eternity breaking into the boundaries of time in ways that shatters time’s grip over us.

This is the arena of the aorist tense.

In this and the two writings that follow, we will look into this ancient verb form—this “timeless tense”—which has the singularly unique power to articulate realities beyond the “horizon” (horízō) of This Age into the timeless structures of eternity.

And in the process, it will not only challenge the preconceptions of our own language as to the nature of time (which for us is the gravitational center, around which all our tenses rotate), but it will, as it were, reach down into the turbulent waters of our lives where we are caught in this “grinding stream” of time’s passage, completely submerged within its maelstrom…and pull us up above the surface…just long enough to behold a new vista existing far beyond the tides of time.

Yet how can this possibly be the case?

How can a mere grammatical tense offer such possibilities of new perception?

From the Ionian school of philosophy to the Attic…to Koine Greek and the New Testament

Maybe this is a reason why Greek ultimately developed into the language of philosophy from Heraclitus’ Fragments in the Ionian period of the 6th and late 5th centuries B.C. (where the Logos first appears in a new light) to its more complex and completed forms in the Attic period of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle?

With these philosophical insights of classical culture being then conveyed to the wider ancient world through the conquests of Alexander the Great, by which point a new dialect had arisen in the form of Koine Greek (from koinós, meaning the "the common dialect" ), out of which the NT writing flowed.

That is to say, by this period the dialectic variations had all fallen to the side (i.e. If you’re from Sparta, you spoke Doric; if from Thessaly, you spoke Aeolic; if from Athens, then Attic, etc., etc.) and a new Lingua Franca appeared in the ancient world.

And so when the “fullness of time was come” (aorist tense) at the time of the 1st century, the NT Gospels, which arose in part out of Syria, Palestine, Rome, Achaia and Ephesus (the former heart of the Ionian School) begin to be composed in Koine Greek, together with the Epistles, which were written to churches stretching from Greek Macedonia (Corinth, Philippi, Thessalonica) through Rome (Romans and the Prison Epistles) to Asia Minor (Ephesus, Colossae, Galatia, etc.) and to the isles of Crete (Titus).

And finally…moving forward into our own history, we may ask whether a return to this classical language ("Ad Fontes") following the maelstrom of the Black Death provided our time-ridden culture a Renaissance and Reformational opportunity to rise up out of the waters of scholastic, encyclopedic, hyper-rationalism to view a point where the timeless structures of eternity had once-for-all intersected with time?

An intersection point which formed the backbone of NT Koine Greek Philosophy and Theology. And the aorist the means of conveying it.

The mechanics of “alignment"

Two final background points.

First, we should note that the mechanics of the Greek language enabled a profound possibility of the most precise expression. With over 800 endings available for a single verb, its linguistic architecture allowed it to convey every conceivable nuance of thought. As such, the language was not a mere system for transmitting information alone.

In its very DNA was the potential to communicate reality both beyond the horizons of This Dimension.

And in so doing, communicate a Reality (with a capital ‘R’) interpenetrating our world from that which lies beyond it.

Communicate a Reality echoing between the Dimensions.

"The Greek language is no 'language' if we are taking this word in the sense of a means of communication...

The Greek language is Logos itself” (Heidegger, What is Philosophy? p. 45).

It is not a “mere word sign;” it is reality “speaking” to us (legein, which is the verbal root of Logos) .

In this argument, the “lover” of “wisdom”—the “philo-sophos,” therefore,

“speaks in the way in which the Logos speaks, in correspondence with the Logos.”

And the outcome of that correspondence is

“in accord with the sophon” (wisdom).

And further,

“This accordance is harmonia” (Ibid. p. 47).

As in to say, the true philosopher and true philosophy itself is entirely dependent on us being in alignment with the harmony and wisdom of the Logos, Who is all the time speaking to us.

And Who, from these three Koine Greek, Johannine words with its verb in the aorist tense, has now definitively entered the structures of our Third Dimension, into the maelstom of its turbulent waters, and Who has fully submersed Himself into all of its limitations, even more, taken onto Himself all of its chaotic injustice and pain, so that He might speak to us from within the structures of our human language

The aorist as the “workhorse”

The second and final background note is that in the NT Koine Greek writings the timeless tense of the aorist became the most commonly utilized tense-mood form (11K occurrences in the over 28K NT Greek verbs). With the Present tense registering in at a far distant second (5K occurrences).

Even so that the aorist tense has been described as the “workhorse” of Koine Greek.

That is to say, the horizonless aorist formed the linguistic backbone of the NT narrative structure, as if to communicate that it is speaking to us from outside the bounds of time, signaling a dimension of completed actions that can now become eternally present to us.

But how?

Again,

And with this introduction we are brought to the discussion of the aorist and the Incarnation.

A central question in the process

In the Prologue to John’s Gospel, we find, in the words of Chrysostom, that with a "brevity of syllables" a mere “fisherman”-become-Apostle is able to penetrate into the eternal mystery of timelessness breaking into time in a manner that is now full and complete for all eternity. As a Hebrew tradesman with no formal education, John’s use of the Aorist tense in the opening verses of his Gospel enables him with only a few words to begin plumbing the philosophical and theological depths of the Incarnation of the eternal Logos in a manner that surpasses the “wisdom of all the world” (Chrysostom, Homily 2 on John, 2.5).

And so, with only two words—egeneto and eskēnōsen: “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us”—the Apostle provides us an entrance into the time-redefining and reality-shifting event of God’s Self-revelation to mankind. By the Apostle’s particular choice of the aorist tense, he is able to communicate to us that the fullness of the eternal Godhead has now once-for-all entered our finite world, fully joining Himself to us in way so complete that it heals our diseased humanity—time present, past and future—and eternally unites the Human with the fullness of the Divine.

Yet in our English translation, there is nothing too distinctive about the actions of these two verbs, other than that they occurred at some point in time past (became…dwelt).

And so we ask,

Why is that the case? Why does our English seem to dilute down and obscure the Greek text?

Or, more specifically and from a different, more positive perspective,

How is it that a mere grammatical tense can convey such timeless philosophical and theological truths with such precision?

The beginnings of an answer: Time vs Completion

The answer lies in how our language conceives of action?

In English, time dominates.

There are 12 ways given to us to describe the action of a verb and every one is confined within the bounds of time, be it past, present or future. As such, each verb is formed by combining the three timeframes (Past, Present, Future) with the four aspects (Simple, Continuous, Perfect, and Perfect Continuous).

Again, time is the conceptual foundation and controlling influence for our entire verbal system. To the degree that we cannot seem to get beyond it. We are locked in time with each English tense, as it were, spatializing verbal action and positioning it upon a clock face.

Greek is different.

It is not so concerned about chronology (When did it happen?), but phenomenology (How did it happen? How is time experienced? How does the speaker view the action within that experience of time?).

Insights from classical grammarians

To this end, Moulton, a pioneer in the study of Koine Greek, emphasizes in his monumental 1906 work, A Grammar of New Testament Greek, that the "time" element in English tenses is, in fact, a rather late development within the evolution of language. In Greek what is primary is "aspect":

“The most important matter is the realization that the 'tenses' originally and primarily defined, not time, but 'kind of action.'

The Aorist, as its name implies, is 'un-defined' [A + horízō]: it treats the action as a point, as a single whole, without reference to its duration” (p. 108).

The central point, then, is that the action of the Incarnation is done, complete.

It need never be repeated. It need not be modified. Nothing need, in John’s later words at the close of Revelation, be “added” to it or “taken away” (Rev 22: 18-19).

This may relate to how Christ’s responds to the Pharisees in the early section of John’s Gospel where he uses the aorist to communicate what were decades of activity. And with this final comment and one further insight from Maximus the Confessor we will draw our introductory exploration into the aorist tense to a close.

A temple built; a Temple destroyed; a New Temple raised up

John, with one aorist word, conveys the finished nature of the building of the Temple in John 2.

When Jesus boldly declares to the Pharisees,

“Destroy this Temple (aorist imperative), and in three days I will raise it up” (John 2:19)

they angrily respond,

“It has taken forty-six years to build this Temple (oikodomēthē: aorist passive indicative), and will You raise it up in three days?” (John 2:20)

The aorist verb simply communicates completion, which may be why the Pharisees have to then add to their statement, emphasizing the length of time…as if to pull Christ down into their time-ridden system:

You dare declare to us that our Temple—the center of our institutional religious power—which took 46 years of our incredibly hard work and diligent labor and human resources to fully complete and finish (oikodomēthē)—This Temple You will raise up in three days?

(τεσσεράκοντα καὶ ἓξ ἔτεσιν οἰκοδομήθη ὁ ναὸς οὗτος,

καὶ σὺ ἐν τρισὶν ἡμέραις ἐγερεῖς αὐτόν?)

And at this question, the Apostle adds the crucial insight:

“But He was speaking of the temple of His body.”

That is to say, the Temple in Jerusalem was not something that could be built by man at all, despite all of man’s fervent activity in chrónos time over five decades.

Nor was man’s religious life centered in this human structure (remembering that religion comes from the Latin word, religio, which means ‘biding’ or ‘connecting’—as in the binding of Heaven with Earth, the weaving of eternity into the structures of time).

Yet John goes further.

After this this extraordinary statement that reorients entirely our religious life, John then adds that the completeness of this weaving together of the eternal God with man in the Incarnation, requires first that the entire action itself be completed.

Therefore, when He had risen from the dead (aorist), His disciples remembered (aorist) that He kept speaking this to them;

and they believed (aorist) the Scripture and the word which Jesus had said (aorist)” (John 2:21-22).

All of this to let us know that it is only at the aorist completion of Jesus’ life, the completion of His Passion and Crucifixion, the completion of His Resurrection, the completion of His Ascension, the completion of all the words which He kept speaking to them, that the disciples can now finally see the fullness of the Godhead in the Person of Jesus and fully believe upon Him unto life.

From the clock time of chrónos to the fullness of kairós time

And with this word we are led finally back to the beginning.

As we quoted at the outset, John declares,

“And the Word became flesh (sárx egeneto: aorist middle indicative)

and dwelt (lit. tabernacled—eskēnōsen: aorist active indicative) among us”

καὶ ὁ λόγος σὰρξ ἐγένετο

καὶ ἐσκήνωσεν ἐν ἡμῖν

The Word which has come down to us out of eternity, Who has fully and completely entered into the structures of this world’s dimensional time (chrónos), Who has taken our flesh into His Body, this Word-become-flesh is fully and finally revealed as the New Temple.

And His 33 years of tabernacling among us within the ticking hands of our world’s clock time (chrónos) is now completed. And at His death, resurrection and Ascension, the action of the Incarnation can be now fully communicated to us in the aorist sense of a single whole where “time” is no longer “the essence" (A. T. Robertson, A Grammar of the Greek New Testament in the Light of Historical Research, p. 834).

Chrónos time has been broken and in its place we are opened to kairós time which speaks to us between the Dimensions.

A final word on Aóristos in Maximus the Confessor: The nexus

Maximus the Confessor wrote that the Incarnation was the

“Center [of all the ages], in which God recapitulates (anakephalaiōsis) in Himself all things;

It is for this mystery that all the ages and the things within those ages have received the beginning and the end of their existence in Christ.”

Then this extraordinary statement,

“For in Christ there was a union of the limit and the Unlimited (the Greek here is aóristos), of the measure and the Immeasurable, of the boundary and the Unbounded, of the Creator and the creation, of rest and motion.

And what, then, is the effect of this integration, this nexus, this religio, where opposite ends of the spectrum meet together?

This union has been manifested in Christ in these last times, fulfilling the plan of God, so that He might lead (lit. “drag”) upwards (anágō) the changeable and divided nature of time into the unchangeable and unified nature of His own eternity.

And that the beginning and the end might meet in Himself, gathering into one (synágō) the things that were previously separated" (Ambigua 7, PG 91, 1084C-D, cf. Eph 1:7-12).

And to this, we simply say,

Amen!