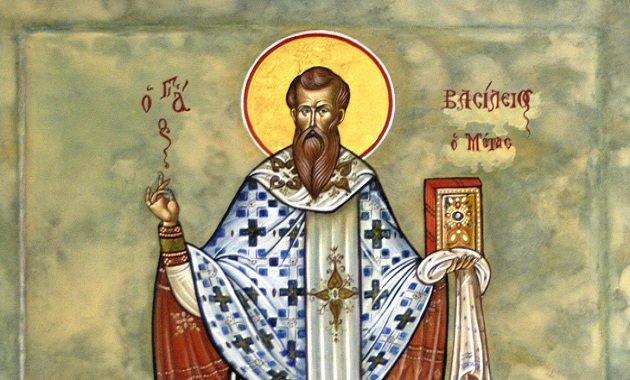

From Arianism to Modern Therapeutic Deism with Basil as our Guide: “He’s not afraid of threats. He’s more powerful than our convictions. Let’s threaten some coward but not Basil,” Part I. Background

[Reading Time: 7 minutes]

Why a speech from the late 4th century…in East-Central Anatolia?

How can it possibly relate to us now?

As to how this relates to our current context, this should become clear upon reading the text below between the Prefect of a Roman Emperor and a preacher/writer/founder of lay communities/constructor of the world’s first hospital system (that was designed, we should add, for the first time in human history to meet the needs of the poor).

As a preface, however, it should be said that there are always, by God’s grace. key figures in ever generation and every century. Basil of Caesarea and Gregory of Nazianzus were certainly those. In our climate of modern, Evangelical Christianity in the West, it can appear that that few are offering to us the Gospel (euangélion) of the victory of Christ Jesus over the powers of This Fallen Age. Rather, the religious climate that takes many into its fold from every tradition seems to offer, rather, an appeasement of a “moral therapeutic deism”, of which we will give a brief overview below.

We mention it because our current cultural climate is not, in actuality, entirely different than prior iterations…even extending as far back as 1600 years ago in Anatolia. Then, as now, the Spirits of the Age (or to use Paul’s own words, the“god of This Age” (ho theós tou aiṓnos) operated to the same extent, exerting an influence which

blinded the minds of men (nóēma) who do not believe, lest the light of the gospel of the glory of Christ, who is the image of God, should shine on them (II Cor 4:4).

The same “god” is still working through the

principalities, powers, rulers of the darkness of this age and spiritual hosts of wickedness in the heavenly places (Eph 6:12).

Who then, to again use Paul’s language, will “wrestle” against them?

Basil was one of those, whose real-life example we offer below so as to spur us on in what lies ahead.

Wrestling against modern forms of Arianism in the cultural emergence of Moral Therapeutic Deism

In Basil and Gregory’s era, they struggled and fought and wrestled against the emergence of Arianism, that is, the prevailing belief that Christ was not, in fact, God but rather a mere creation by God, whose exemplary life, nevertheless, offered good moral guidance to the masses. This false doctrine held great sway over the Roman Empire even after its denunciation as a heresy by the Council of Nicea (325 A.D.). With greater levels of ferocity, the Emperors, bishops, priests and people alike, who were were caught in its blinding grip, fought vehemently to maintain its powerful hold, weaponizing (as we shall see below) against any that defied them.

And even with great resistance (again, as we shall see below), the influence of Arianism continued…which we should note has passed through the ages into modern Western Christendom. There is, to make it less abstract, the hold of Mormonism, which puts forward a growth globally to over 17 million. For them, Christ is “the firstborn spirit son of God”, [LDS Doctrine of the Gospel Student Manual, 9] and “among the spirit children of Elohim” [Smith, Gospel Doctrine, 70].

Then, to note another, there are the Jehovah’s Witnesses whose worldwide number exceeds 19 million. For them, “Jesus is the sole direct creation of God” Watchtower, 5).

Even within the Protestant church, to draw it from the realm of splinter heresies into a main frame of Western Christendom, there is the dimension of Modern Liberal Protestantism which arose out of Higher Criticism that denied the realities of the virgin birth and resurrection of Jesus with all associated miracles, etc., etc…

The point is that in all of these heresies, both past and present, is simple:

Jesus is not fully God.

And He is not the Word of God enfleshed, whose full assumption of the totality of our humanity is the ontological basis of our eternal salvation.

And further, He is certainly not our eternal judge (despite the claims of Jesus,“For the Father judges no one, but has committed all judgment to the Son…” John 5:22). Rather, He is simply a good man whose beautiful and inspiring teachings can help us.

Now enter Moral Therapeutic Deism.

A definition

This rather technical term arises out of the research conducted by sociologists, Christian Smith (Notre Dame) and Melina Lundquist Denton (UNC-Chapel Hill; now UT-San Antonio), who synthesized their conclusions from in depth analysis of The National Study of Youth and Religion [NYSR], the largest and most detailed such study ever undertaken, which, in their words, “affords an important and distinctive window through which to observe and assess the current state and future direction of American religion as a whole.”

Their conclusion, in short, was that there is the emergence of a “de facto dominant religion,” which they described as “moral therapeutic deism” (p. 162).

Moral: Be Good;

Therapeutic: It will help you;

Deism: And God, “a Divine Butler and Cosmic Therapist” (p. 165) will help when things get tough, but will otherwise keep a safe distance from your personal affairs.

Lundquist Denton and Richard Flory wrote a follow-up article in which they updated and further honed the definitions of this de facto religion through in depth interviews of these teenagers now turned “emerging adults.”

Seven spiritual beliefs of young adults

“Emerging adults,” they contend,

consistently frame their moral decision-making as something they “just know” or “feel.” A decision is right or wrong based on tacit knowledge that is felt rather than rationally articulated.

As to where such moral knowledge actually comes from,

Their beliefs remain “taken for granted” or are an assumed part of their lives, and they are more or less accepting of their faith as they have experienced it growing up. Ideas about God and faith are things they “just know.”

As such, there is no systematic, externally verifiable basis for one’s belief system:

Mine just is and yours just is.

And we simply “cobble” it all together “into a highly individualized religious/spiritual perspective tailored to [our] own needs” as we

borrow and develop beliefs and morals from different religious traditions and larger cultural currents, without any need for greater involvement in or commitment to any particular religious tradition or for any actual coherence with these traditions.

Below are the “seven core tenets of this general outlook.” (See the Appendix below for the complete description of each.)

1) Karma is real (with an “undefinable supernatural force” generally working with a “cosmic logic” in order to “make for a just and ordered world”)

2) Everybody goes to heaven

3) Just do good (“That is, If you treat people well, you increase your odds of going to heaven.”)

4) It’s all good (“People can believe whatever they want or act how they want…as long as they aren’t hurting others.” The “two key tenets” that are “exemplified in this approach” are “tolerance and acceptance.”)

5) Religion is easy (as it “imposes no significant demands” on us and as such, truly and literally is, the “broad and easy way.”)

6) Morals are self-evident (“you just know, or feel, what is right and wrong—even though they’re all relative.”)

7) No regrets (“Certainly, some acknowledge decisions and choices they may have made that weren’t great, or things that didn’t work out, or opportunities they wish they had pursued. But, taken together, all of those experiences and decisions make a person who they are, and nobody wants to be any different from who they understand themselves to be. In turn, this helps to explain the preference among emerging adults for religion with no demands; such a religion would not require a person to confess or repent of sins or otherwise change their choices or behavior.”)

With this overview of the modern dimensions of the Arian heresy, we now turn back to its antecedents at the time of the great Cappadocian Father, Basil with his extraordinary response, which we will cover in Part II.

Appendix: Seven spiritual beliefs of young adults, Melinda Lundquist Denton and Richard Flory, The Christian Century, April 8, 2020:

Karma is real. In our interviews, many emerging adults explicitly mentioned their belief in karma, while others expressed a similar idea, such as “everything happens for a reason,” or some related perspective that suggests belief in some spiritual or perhaps undefinable supernatural force that generally works to make for a just and ordered world.

Their view of karma is a popularized version that is not particularly true to its actual religious meaning. It is a way to explain how the bad things and the good things that happen in their lives tend to balance out. The concept of karma operates as a quasi-moral code that provides them with both some sense of the necessity to treat other people well or to otherwise do good (or at least not harmful) things in the world and an explanation—a nonreligious theodicy of sorts—for why good people ultimately end up having good things happen to them and bad people end up having bad things happen to them.

Everybody goes to heaven. In the view of most emerging adults, going to heaven is generally a result of how you act in the world rather than being related to any specific religious teachings about heaven, hell, or the afterlife. While emerging adults tend to express a belief that people go to heaven because of their good works on earth, they also believe it is the rare person who does not go to heaven.

Rather than there being some sort of ledger that weighs a person’s good actions against their bad actions—such as in their version of karma—being kept out of heaven is determined by whether a person performs actions that are unforgiveable. This punishment is mostly reserved for murderers, rapists, and other people who have hurt another person in a significant way.

Just do good. The golden rule for emerging adults is to be good to other people and to treat them fairly. This is related to their beliefs about karma and who goes to heaven as well as to the conviction that the most important moral code is not to hurt anyone. That is, if you treat people well, you increase your odds of going to heaven. But, more than this, being good to others is an expected way to live and act, although the particular elements of “treating others well” are largely undefined. This outlook has persisted throughout the course of this ten-year study, as exemplified most memorably when one teenager told us that his perspective on life boiled down to: “You know, don’t be an asshole.”

It’s all good. We’ve all heard the saying, “It’s all good,” usually as a replacement for saying something like, “Everything’s OK,” or “Don’t worry about it.” This phrase also highlights how emerging adults strive to live their lives as nonjudgmentally as possible.

For emerging adults, “It’s all good” means that other people can believe whatever they want or act how they want—and as long as they aren’t hurting others, it is seen as no problem. Two key tenets of life are exemplified in this approach: tolerance and acceptance. It doesn’t matter if they agree with others on religion, politics, whatever; it’s all good.

Religion is easy. According to most emerging adults, maintaining one’s religious life is “pretty easy,” primarily because their understanding of religion imposes no significant demands on them. For emerging adults, one takes what one wants from religion and leaves behind anything that is irrelevant or inapplicable to one’s life or that goes against one’s own sense of what is right or wrong. Emerging adults don’t want religious organizations to tell them what to do or believe, particularly on issues like gender identity, sexuality, abortion, and marriage.

Further, religion and spirituality constitute just one part of life, and not necessarily the most important one. In the end, you get—or take—what you want from religion. Again, some people are more religious, some more spiritual, but overall, whatever they are, it’s all good. And the equanimity is easy to maintain.

Morals are self-evident. Emerging adults adhere to the idea that morals and values are self-evident—you just know, or feel, what is right and wrong—even though they’re all relative. In some ways, this is related to emerging adults’ perspective on the ease of maintaining their religious and spiritual lives. Because morals and values are self-evident, they ultimately don’t present any sort of dilemma when confronted with making a moral decision—you just know.

This all sounds pretty relativistic, and in some ways it is—although there are limits. Emerging adults also say that it is not OK to cheat in order to benefit personally. But this, too, is self-evident for emerging adults because it would go against their commitment to treating others well.

No regrets. If “It’s all good” is one mantra, a related one is “No regrets.” In fact, having regrets is something that most emerging adults at least imply would be a negative thing in their lives. This seems to be related to their belief in karma, in that there is some force, or cosmic logic, that evens things out and helps make sense of the inequities and bad things that happen to a person. All of the life experiences a person has had are what have made them who they are, and if any of those were changed, they would be a different person. Certainly, some acknowledge decisions and choices they may have made that weren’t great, or things that didn’t work out, or opportunities they wish they had pursued. But, taken together, all of those experiences and decisions make a person who they are, and nobody wants to be any different from who they understand themselves to be. In turn, this helps to explain the preference among emerging adults for religion with no demands; such a religion would not require a person to confess or repent of sins or otherwise change their choices or behavior.