Hagiázō (ἁγιάζω) “Hallowed,” Part I. From Earth to Heaven, the Human to the Divine, Time into Eternity: A Psalm of Ascent

[Reading time: 11 minutes]

Hagiázō (ἁγιάζω)

28 occurrences in the NT:

8x in the Gospels

2x in Acts

9x in the Pauline Epistles

7x in Hebrews

1x in I Peter and 1x in Revelations

Etymology and Dictionary Definition

From hágios (ἅγιος): That which is set apart from the common or profane due to its intrinsic relation to the Divine-> Holy, sacred, pure.

Further derived from hágos (ἄγος), of which there are no uses in the NT or LXX but from classical Greek literature it can mean that which produces awe, reverence and fear, on the one hand, or that which is an abomination and cursed, on the other. In the first instance, it is the mysterium tremendum et fascinans—a mystery both terrifying and fascinating as it ushers us into a sacred, other worldly dimension which both mystifies and overwhelms our fallen senses.

And yet for those who are caught in state of defilement, it becomes a plague.

We only need think here of the tragic life arc of Oedipus Rex. Saved from infanticide, he rises to the level of has unknowingly killed his father and married his mother, the whole city of Thebes is taken up into his defilement such that the people suffer a

”Plague of power,” the crops waste away, herds fail, the women become barren, youths languish and “Hell's house becomes rich with steam of tears and blood” (v. 14-57).

The once savior of Thebes, “world-honored” for freeing the people from the devouring terror of the Sphinx’ riddles of death, then vows to rid the city of this blight, blind to the reality that it is he himself who has brought this hágos upon the city by his parricide and incest, which now pollutes everything it touches—A ”horror” (hágos) so unspeakable that it is a “stain” on the very light of the Sun, which “never Mother Earth may touch” nor “God’s clean rain” wash away (1424-1429).

Only by his

Taken together, hagiázō means, therefore, to make holy and sacred by setting it apart due to the nature of its Holy Divinity or to its intrinsic relation to the Divine. The Lord is hallowed because He is the Holy One. The “saints” are made holy in to their relation to the Lord.

Though we will trace its meaning back through the OT in our next writing, we will confine ourselves in this first writing to its opening occurrences in the Lord’s Prayer.

Summary Synthesis

The use of hagiázō its opening use in the Lord’s Prayer immediately reveals the tension between the Eternal/created, the Divine/human, the Heavenly/earthly, and the Perfect/fallen realities that operate within This Fallen Age.

Separated from JHWH by our own ancestral sin and with legions of the seed of the serpent arrayed against us, hagiázō opens us back to God in ways that can usher us—not back into the Garden—but forward into the New Creation.

And it does so by leading us to to truly pray, begging for the Eternal Perfection of Heavenly Light and Truth to break into our present moment; begging for Surrounded by the darkness and deceit of this world’s systems, we asking for the Spirit to bring the Kingdom of God within us (Lk 17:21), we who are now surrounded by the darkness and deceit of the chaotic floods that rise over us.

As God’s name is “hallowed”, Heaven and earth meet.

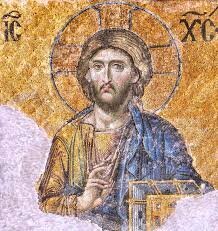

And this point of contact, this meeting place, this nexus point, is in the Messianic King, Whose Body is the Temple where God fully meets man; where God redeems fallen humanity; where God empowers mankind through His Eternal Spirit to live the New Creational life here and now in This Fallen Age.

Detailed Analysis

The Heaven/Earth, temporal/eternal distinctions made clear in its opening usage

The initial use comes in the opening petition of the Lord’s Prayer:

“Our Father,

You Who are in the Heavens,

may Your Name be hallowed (hagiázō, Mt 6:9).

Πάτερ ἡμῶν,

ὁ ἐν τοῖς οὐρανοῖς,

ἁγιασθήτω τὸ ὄνομά σου

In the Lucan version, it should be noted that this petition is abbreviated to simply

“Father

may your name by hallowed” (Luke 11:2)

πατερ

αγιασθητω το ονομα σου

In the former case, the distinction between the Eternal/temporal, the Divine/human, the Heavenly/earthly, the Perfect/fallen is made explicit in the Father’s position of perfection within the eternal Heavens.

In the latter, this is assumed.

Focusing on the phrase “in the Heavens,” we can trace its usage through the early Psalms of Ascent, where all of the above distinctions become progressively clearer—created/Eternal, the human/Divine, earthly/Heavenly, fallen/Perfect. In Part 1, we will examine this tension within Psalm 120, which take us from the Genesis through the Prophets into Revelation.

Psalm 120

The initial Psalm of Ascent opens with the cry of the Psalmist out of distress to His Covenant God, JHWH—the Eternal I AM.

“In my distress I cried (qarah) to the LORD,

And He heard (anah) me” (Ps 120:1a).

And what does he ask/pray/beg?

“Deliver my soul, O Lord, from lying lips

And from a deceitful tongue” (120:2).

Trapped on all sides by the the deceit and violence of men in This Fallen Age, he focuses his plea on the call for Divine Judgment on the “false tongue” (v 3-4). In pleading for this, he makes his grievous position even clearer.

“Woe is me, that I dwell in Meshech,

That I dwell among the tents of Kedar!

My soul has dwelt too long

With one who hates peace.

I am for peace;

But when I speak, they are for war” (120:5-7).

In examination of their uses in the OT, Mesech, on the one hand, and Kedar, on the other, both reveal the horror of the satanic forces that are arrayed against God’s people.

From Gen 10 to Kedar and Ishmael

From the Table of Nations in Genesis 10, Mesech is first identified as a son of Jepheth, whose brothers are none other than Magog, Tubal, Tiras, Gomer, Madai, and Javan (more on this below).

Kedar are the sons of Ishmael, whose “hand,” it was prophesied, would be

“against every man, and every man’s hand against him” (Gen 16:12-> Gen 25:13).

As has been said, it was a prophecy of one that would rage in

“war of all against all” (bellum omnium contra omnes).

Regarding Mesech, their nature as the ancient line of the seed of the serpent is more fully revealed in Ezekiel.

From slave-traders to Death and Hell

There, they are initially presented as slave-traders benefiting from the greed and wealth of Tyre:

“Javan, Tubal, and Meshech were your traders.

They bartered human lives and vessels of bronze for your merchandise” (Ezek 27:13...Rev 18).

Later their name becomes synonymous first with uncircumcised pagans, then with death and Hell itself.

“There is Meshech, Tubal, and all her multitude:

Her graves are round about him:

All of them uncircumcised, slain by the sword, though they caused their terror in the land of the living” they are now “gone down to hell with their weapons of war” (Ezek 32:26-27).

To “Gog, the Land of Magog”

And as the prophecy continues, there is the call for judgment upon what is now the land of Gog and Magog, who truly “hate peace” and are “for war.”

“Son of man, set your face against Gog, the land of Magog”

And who is Gog, the land of Magog?

It is, interestingly enough, finally identified as a person, the

“chief prince of Meshech and Tubal”

Against him, the Prophet is called to prophecy,

‘Thus says the Lord God:

Behold, I am against you, O Gog, the prince of Rosh, Meshech, and Tubal” (Ezek 38:2-3).

From Gog, Meshech and Tubal to the Last Battle

This prophetic pronouncement of judgment forms the background for the Last Battle and Final Judgment in Revelation 20.

When Satan is “released from his prison,” he immediately goes out

“to deceive (planáō) the nations which are in the four corners of the earth, Gog and Magog,

to gather them together to battle (synágō…the satanic synogogue, we might say), whose number is as the sand of the sea” (Rev 20:7-8).

These massive satanic forces then surround the “camp of the saints” and the “beloved city” with a view towards its total destruction (20:9a).

Just then, however, before even a sword is drawn,

“fire comes down from God out of heaven and devours them” (20:9).

Our cry in the midst of battle to a God Who hears: Encouragements to pray from Edwards

From this great war between the seed of the woman and the seed of the serpent, which is followed through the History of Israel into the age of the Church and culminates in this Final Battle, we now look from it back to the suffering Psalmist, still in the midst of the battle, surrounded on all sides by men of deceit and war.

From this position, all the Psalmist can do is cry out to the Eternal God—JHWH, the One Who made an Eternal Covenant with His people.

And this God “hears” (Ps 120:1).

In the words of Edwards on this great impetus of the Psalmist to pray, he directs our eyes up to God, Who

“sits on a throne of grace”

Where

“there is no veil to hide this throne, and keep us from it.

The veil is rent from the top to the bottom; the way is open at all times, and we may go to God as often as we please.

Although God be infinitely above us, yet we may “come with boldness” where we “obtain mercy, and find grace to help in time of need” (Heb 4:14).

He continues with even more encouragements to prayer, declaring that the Scripture reveal to us that the

“voice of the saints in prayer is sweet unto Christ;

He delights to hear it.

He allows them to be earnest and importunate; yea, to the degree as to take no denial, and as it were to give Him no rest, and even encouraging them so to do.”

From the “Watchers” to Jacob to those who take the Kingdom “by force”

Here, Edwards turns us from the Prophet Ezekiel to Isaiah,

“I have set watchmen upon thy walls, O Jerusalem, which shall never hold their peace day nor night: ye that make mention of the LORD, keep not silence,

And give him no rest, till he establish, and till he make Jerusalem a praise in the earth” (Is 62:6-7).

With such an OT call to perseverance in prayer, Edwards draws us to the words of Jesus.

“Christ encourages us, in the parable of the importunate widow and the unjust judge (Luke 18:1-8).

So, in the parable of the man who went to his friend at midnight (Luke 11:5-8).

Thus God allowed Jacob to wrestle with him, yea, to be resolute in it;

“I will not let thee go, except thou bless me” (Gen 32:26).

It is noticed with approbation, when men are violent for the kingdom of heaven and “take it by force” (biázō, Mt 11:12).

Thus Christ suffered the blind man to be most importunate and unceasing in his cries to him (Lk 18:38-43).

A violent entrance…into free access

Edwards then concludes, having taken us across the span of Scripture, from the Psalms of Ascent into the Epistle to the Hebrews and from the Pentateuch and Prophets through to the Parables of Christ,

“The freedom of access that God gives, appears also in allowing us to come to Him by prayer for every thing we need, both temporal and spiritual; whatever evil we need to be delivered from, or good we would obtain:

“Be anxious for nothing (merimnáō)

Lit. ‘Be not divided and split into parts’ (merízō)

but in every thing by prayer and supplication, with thanksgiving, let your requests be made known to God” (Phil 4:6).