The Fivefold Path of Reconciliation: Part III. The “change” effected not by fallen man but by God in Christ (as we pass from suppression to confrontation and victorious union)

[Reading Time: 16 minutes]

Review

In the first two installments of this word study, we traced the opening uses of allássō through Acts 6-7 then Romans 1, where we saw how change is manipulated by the fallen mind of This Present Age.

And here we found that the central focus was invariably control.

Fallen man will use every human method at their disposal to ensure the specific outcome they so desire. And while that outcome may, in fact, occur, another outcome happens in its wake. This outcome, however, operates on a far different, far deeper level...for better or for worse.

On the first, visible level, as in the case of Stephen and the religious establishment, the first deacon’s ministry was indeed stopped; and religious control over the populous was maintained…at least initially.

Yet on a deeper level—a spiritual, initially unseen, level—the brutal murder and martyrdom of Stephen not only failed to halt the spiritual progress of the NT Church, but moreover, as the book of Acts bears full witness, functioned in a way that planted the seeds for its future growth.

And need we mention that these levels were, likewise, in full operation in the false accusations, unjust condemnation and violent crucifixion of Jesus?

Yet, there are still more levels.

The next use of allássō demonstrates an even deeper effect that operates within the mind/heart/soul/nous of fallen man as a direct result of their manipulated control. While, on the surface their actions do, in fact, secure a desired result, Romans 1 shows with terrifyingly surgical and psychoanalytic precision that on a much deeper level their actions began a transformational process that conformed their inner person into the image of Hell itself. As such, in Paul’s language, when they

“changed (allássō) the glory of the uncorruptible God into an image made like to corruptible man”

then

“exchanged (metallássō: From meta + allássō) the truth of God for the lie, and worshipped and served the creature rather than the Creator” (Rom 1:23, 25),

God then “gave them over” (paradídōmi) to the horror of their controlling passions (1:24, 26, 28). And in the final analysis, the outcome they ultimately secure is not one that enables tighter control over someone else, but rather one that leads to their own spiritual devolution, as they become

“foolish, faithless, heartless, ruthless” (1:31).

And so in its opening uses, allássō is demonstrated to operate on multiple levels (physical, mental, emotional, moral, spiritual) with vastly different effects. But, we may posit that these effects ultimately depend on one thing and one thing only:

The relation of that person’s heart to control.

When allássō is under the control of fallen man, his manipulated, engineered effects—while they can obtain their immediate end—nevertheless, place him on a pathway to his own spiritual dissolution and death. When, however, man’s relation to allássō is one, not of control, but of obedience; one not of external religiosity, but of a hidden life of faith operative in fearless waiting upon God, the outcome is life-giving—even in the face of death.

Review in One Sentence

To summarize this in as straightforward a way as possible, whenever we seek to control any change in another person, we not only fail to do so, but through it we begin to take into ourselves the operations of Hell itself.

Allássō in I Corinthians

We move on now to the next two two uses in I Corinthians. where we see something very different happening, something that is, in a sense, the complete opposite.

Here, allássō operates on the level, not of the fallen mind which seeks to control another in a way that actually works the dissolution of Hell into their inner soul, but rather on the level of the eternal Kingdom of God, where it effects the glorious transformation of the Gospel through and in Christ.

Summary Synthesis

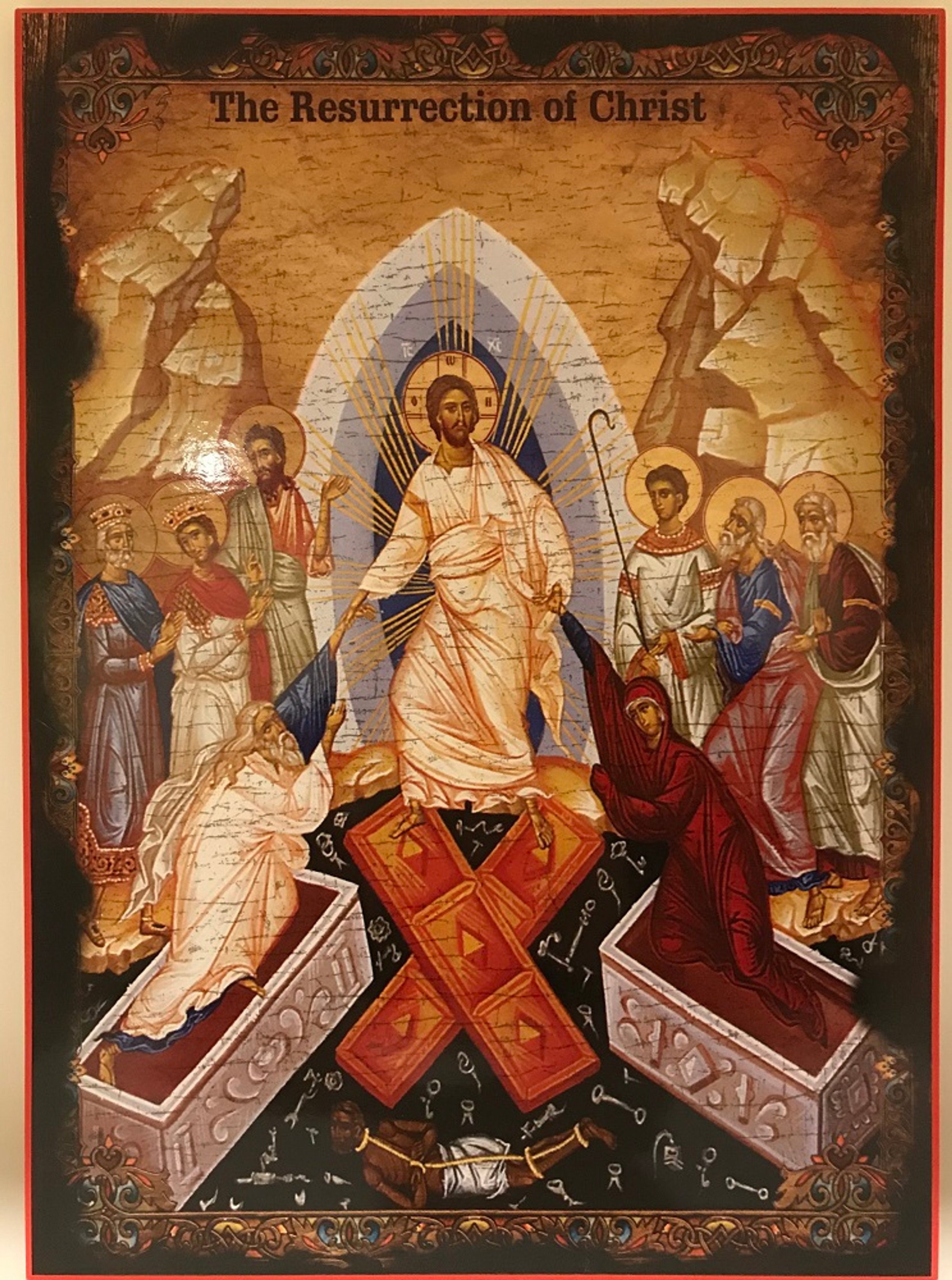

The next instances of allássō in I Cor 15 are given to us in the passive tense—“shall be changed”—with the setting being Christ’s glorious working in the soul and body of believers to transform them into His resurrection image.

Following the text of the chapter forward from the beginning, Paul opens with a declaration of the Word that he has “received” of Christ’s death and resurrection “according to the Scriptures” as well as His appearances to the Apostles, the fledgling Church, and not least of all, Paul. And the parousía of Jesus to Paul has a paradoxical effect:

While it heightens his own recognition of his sin as he experiences greater glimpses of the Holiness of God, this leads not to shame, but rather a renewed understanding of the Grace of God towards him.

This vital experience will be foundational to what Paul will then teach on the nature of the Resurrection and its transforming effects in the soul of man.

Confronting the utterly hopeless, gnositc dualist strand in the early Church that denied Christ’s resurrection, Paul goes on to demonstrate that His rising from the dead was the linchpin for every other doctrine of the Christian Faith: From the doctrine of sin and the Fall to the doctrine of salvation and sanctification, all the way to the doctrines of eschatology. From here he enters into a depth of analysis into how these all relate to the transformation of the believer from the fallen state into a glorified, eternal union with their risen Savior.

In short, how

The body is sown in corruption, it is raised in incorruption.

It is sown in dishonor, it is raised in glory.

It is sown in weakness, it is raised in power.

It is sown a natural body, it is raised a spiritual body.

In these great paradoxes operating on the physical and spiritual, the temporal and eternal, planes, we are introduced to the reality that as we follow Christ in obedience, we will not control any change in ourselves or another; but rather, “we shall be changed…and we shall be changed.”

Detailed Analysis

The next two occurrences of allássō come in the penultimate chapter of I Corinthians in what has been called the “Resurrection Chapter.” And given what we know about the effects of man’s control of allássō, it is very instructive that both of these uses occur not in the active, but in the passive, form.

The experiential reception of God’s Grace in humility that drives the working-out of salvation

Paul had declared at the outset that the “Gospel” he had “preached” unto them had the power to “save,” if they “receive” it and “stand upon” it and “hold” it “fast” (katechó,15:1-2). For that which he offered to them he himself had “first received” (15:3a).

And what Word did he receieve?

that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures

and that He was buried

and that He rose again the third day according to the Scriptures (15:3b-4).

After next speaking of Christ’s appearance to “Peter” and “the twelve” then “five hundred brethren” and “all the apostles,” which all vindicated that revelatory Word Paul had preached, Jesus finally appears to him, “as one born out of time” (ektrauma, lit. “out of a trauma,”15:5-8). This bodily appearance of the risen Christ, then, forms the basis of all that he will write and teach on the resurrection.

That is to say, it is not theoretical or abstract; it is experiential. And even more, it is traumatic, just as in the case of Stephen when he met his risen Savior. Yet, it is a trauma, a wounding, that ultimately brings life.

And what effect did Christ’s parousía have upon Paul?

Does it lead to his elevation in pride? For he is the final one to whom the risen King comes.

No. Precisely, the opposite:

For I am the least of the apostles, who am not worthy to be called an apostle (15:9a).

And why is that?

because I persecuted the church of God (15:9b)

That is to say, it leads him to a deep recognition of his own sin and unworthiness before the Holiness of God. Pride simply cannot operate in a true believer when he or she meets the risen Lord Who eternally “bears in His own body” the wounding of man’s sin.

And if pride is operating, the question for us, then, is,

Have we actually met God?

Then, in a way that seems only possible with the inner-working of the Holy Spirit, this recognition of sin and guilt does not lead to shame and its manipulation in the soul of man (“Look what you did!” “How could you?” “How dare you?” “No good person could do that!”).

No, it leads first to a stillness that comes from a deeper, experiential understanding of God’s mercy, God’s grace.

But by the grace of God I am what I am (15:10a).

Then, paradoxically, such stillness fuels an inner drive to labor and spend whatever a person has in the working-out (katergadzomai) of that Grace; because

His grace toward me was not in vain (15:10a).

So, he

labored more abundantly than they all

Yet, as one who had come to know full well that it was all the time

not I

but the grace of God which was with me (15:10b).

This vital experience is foundational to what Paul will then teach on the nature of the Resurrection and its transforming effects in the soul of man.

No resurrection; no witness; no hope…only deceit and supression

In confronting the false, or more precisely, gnostic teaching in the Corinthian church that Jesus, in fact, was not “raised from the dead” and that “there is no resurrection of the dead” at all (15:12-13), Paul shows that such a position means that

empty (kenós: empty, hollow, vain) is our preaching,

and empty (kenós) is your faith (15:14).

Even more,

If Christ is not risen, vain and utterly futile (mátaios) is your faith.

And why?

For you are still in your sins! (15:17)

If Christ did not suffer and die; if He was neither buried nor rose again from the dead, sin can in no way be dealt with. And so, we weak, little fallen, unstable creatures are left to somehow deal with it on our own.

As an aside, could this possibly be a reason why early psychoanalysis held the position that religion had been utilized by its adherents, not to heal the complex structures of a their personalities, but rather to suppress out of view the actual realities of the darkness that lay hidden within their own person? That the psychological effects of religion were not to bring salvation but to enable its followers to suppress their personal darkness deep within the unconscious where it could remain locked away?

Yet locked away and hidden from view, the darkness thus remained unconfronted and undealt-with such that it could, paradoxically enough, as they came to realize, exert a nearly all-encompassing power over a person’s moment-to-moment decision-making and behavior.

From the hopelessness of gnostic dualism to the glorious doctrines of our faith

From an examination of this “most pitiable” position (15:19) of the gnostic-Christian stance, Paul returns to the foundations of Orthodoxy. First, the doctrine of the resurrection:

But now Christ is risen from the dead, and has become the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep (15:20).

Then, its relation to sin and the Fall:

For since by man came death, by Man also came the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ all shall be made alive (15:21-22).

Then, the work of sanctification, conforming our inner persons to the image of our resurrected Savior:

But each one in his own order: Christ the firstfruits, afterward those who are Christ’s at His coming (15:23).

And finally, the doctrines of eschatology and the “last things” (eschaton):

Then comes the end, when He delivers the kingdom to God the Father, when He puts an end to all rule and all authority and power.

For He must reign till He has put all enemies under His feet (15:24-25).

And His defeat of Death itself:

The last enemy that will be destroyed is Death (15:26).

We will return in a moment to this personification of Death first presented to us in Hosea, but for now, Paul applies all of this seemingly “detached doctrine” to the flesh-and-blood realities of our lives.

And Why? For, the believer, he reveals,

stands in jeopardy every hour (15:30).

But shouldn’t we be strong and powerful in this life through and in the resurrected Christ?

I affirm, by the boasting in you which I have in Christ Jesus our Lord, I die daily (15:31; cf. Ps 44:22-> Rom 8:36).

That is to say, in This Present Age, we will experience what our Savior experienced—death. For He only calls us to take up our cross, after He Himself took up His cross and was raised upon it by our own hands.

If we reject this narrow and hard, suffering path, all that is left for us is the vanity of this passing age.

If, in the manner of men, I have fought with beasts at Ephesus, what advantage is it to me? If the dead do not rise, “Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die!” (15:32)

After, therefore, calling us to “awake to righteousness, and not sin,” which, he adds, can only happen when we “have the knowledge of God,” he presents in fuller detail the doctrines of the resurrection life.

An objection stated and answered with the mysteries of transformation revealed

He begins with the objection:

But someone will say, “How are the dead raised up? And with what body do they come?”

And without mincing words, he immediately proclaims,

Foolish one, what you sow is not made alive unless it dies (15:36).

Our death is fundamental; it is a sine qua non to all that follows. Without it, no resurrection is possible.

And only at this point does he open to us the divine realities at work. For there are different bodies:

celestial bodies and terrestrial bodies;

but the glory of the celestial is one, and the glory of the terrestrial is another (15:40).

And, as such, the glory of each is different—or more precisely, its pathway to glory is different:

The body is sown in corruption, it is raised in incorruption.

It is sown in dishonor, it is raised in glory.

It is sown in weakness, it is raised in power.

It is sown a natural body, it is raised a spiritual body (15:42b-43)

In short,

There is a natural body, and there is a spiritual body.

And so it is written, “The first man Adam became a living soul” (psychḗn zosan.) The last Adam became a life-giving spirit (pneûma zōopoioun [From záō + poiéō: That which “gives life,” 15:44b-45).

Yet, as already noted, there is an inherent order:

The spiritual is not first, but the natural, and afterward the spiritual.

The first man was of the earth, made of dust; the second Man is the Lord from heaven.

As was the man of dust, so also are those who are made of dust; and as is the heavenly Man, so also are those who are heavenly (15:46-48)

Then, the pathway is elucidated for those “borne in the image of the dust”:

And as we have borne the image of the man of dust, we shall also bear the image of the heavenly Man (15:49).

But we have to come to terms with the fact

that flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God; nor does corruption inherit incorruption.

Such an “inheritance” is impossible.

And Why?

In this answer, we have (at long last:) the third and fourth occurrences of allássō:

Behold, I tell you a mystery (again, mystḗrion—that sacramental mystery which, not words, but only living experience can encompass):

We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed (allássō)—

In a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet.

For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised incorruptible, and we shall be changed (allássō, 15:51-52).

“We shall be changed…and we shall be changed…”

And the summary:

For this corruptible must put on incorruption, and this mortal must put on immortality (15:53).

The prophecy of Judgement transformed through the Messiah

And we return in the final verses to Hosea:

So when this corruptible has put on incorruption, and this mortal has put on immortality, then shall be brought to pass the saying that is written:

“Death is swallowed up in victory.”

Then the well known quetions:

“O Death, where is your sting?

O Hades, where is your victory?”

In the original language of the Prophet Hosea, however, it should be noted that he is actually speaking these lines not in encouragement, but as judgment upon Israel:

Will I deliver them from the power of Sheol? No I will not!

Will I redeem them from death? No, I will not! (Hos 13:14a).

Only after this does he then declare the above lines, whose force in the Hebrew is,

O Death, bring on your plagues!

O Sheol, bring on your destruction

My eyes will not show any compassion (nokham, NET, 13:14b).

As Paul explains following the redemptive work of the Messianic King, judgement had been imminent because

The sting of death is sin, and the strength of sin is the law (15:57).

“But” now the Apostle declares,

But thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ (15:58).

There is no more judgment, no more condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus. Death has no power; the grave can not bring its destruction. And we shall experience the great compassion of God in our transforming union with Christ which will change us.

Yet—and this is the point of these three introductory posts, the change is experienced only as we experience Christ’s redemptive work. We don’t effect any change; we don’t control any transforming movement, not in ourselves, and certainly not in another.

We simply follow the hard and narrow path of obedience, knowing that “we shall be changed…and we shall be changed.”

Amen! and Amen!

So may it be!