Psalm 63, “A Psalm of David, when he was in the wilderness of Judah” (Miḏbār [מִדְבָּר]): From the Wilderness of Paganism to “Affliction” (anah [עָנָה]) to a Pit to Covenantal life in the Passover

[Reading Time:

Introduction to Psalm Superscriptions: 4 minutes

Word studies on

Miḏbār: 7 minutes

Anah: 7 minutes]

The Superscription

With the introduction to kataphysic inquiry and epistolomological inversion in our prior writing, we now move into the text of Psalm 63. Our focus here will be on the superscription, as noted, but we will begin by quoting the Psalm in its entirety:

A Psalm of David when he was in the wilderness of Judah.

1 O God, You are my God;

Early will I seek You;

My soul thirsts for You;

My flesh longs for You

In a dry and thirsty land

Where there is no water.

2 So I have looked for You in the sanctuary,

To see Your power and Your glory.

3 Because Your lovingkindness is better than life,

My lips shall praise You.

4 Thus I will bless You while I live;

I will lift up my hands in Your name.

5 My soul shall be satisfied as with marrow and fatness,

And my mouth shall praise You with joyful lips.

6 When I remember You on my bed,

I meditate on You in the night watches.

7 Because You have been my help,

Therefore in the shadow of Your wings I will rejoice.

8 My soul follows close behind You;

Your right hand upholds me.

9 But those who seek my life, to destroy it,

Shall go into the lower parts of the earth.

10 They shall fall by the sword;

They shall be a portion for jackals.

11 But the king shall rejoice in God;

Everyone who swears by Him shall glory;

But the mouth of those who speak lies shall be stopped.

The superscription is,

A Psalm of David when he was in the wilderness (Miḏbār [מִדְבָּר]) of Judah.

Before we attempt a synthesis of the Hebrew word translated as “wilderness” (miḏbār), we should probably ask the more general question:

Are the superscriptions in the Psalms inspired?

That is to say, should we evaluate them in the same way we evaluate Scripture? (i.e. perform word studies on the text, derive insight and spiritual direction from them…?). Or should we, rather, see them as later scribal additions, the truth and validity of which remains in question?

An introductory word on superscriptions in the Davidic Psalms

In the Psalms there are 13 historical superscriptions that refer to David’s life. Psalm 63 is one of those (as well as Psalms 3, 7, 18, 34, 51, 52, 54, 56, 57, 59, 60 & 142). As noted, if these superscriptions are considered a part of the inspired, Hebrew Bible, then our response to them would be the same as to the corpus of Scripture.

If they are not, however, such that they are nothing more than scribal additions and rabbinic interpolations made over the centuries, we should make a note of their questionable historicity then quickly pass over them to the body of the Psalm itself. (…Or, worse, we should reject their authenticity altogether and insert into the historical context our own modern theories, be they derived from a form-critical approach, a cult-functional approach, etc., etc…).

If, however, there is, at the very least, a possibility of divine inspiration (as for example could be argued from the fact that the title of Psalm 18 is found in II Sam 22:1, the Davidic authorship of Psalm 110 is confirmed by Jesus Himself in Lk 20:42, etc.), then these historical superscriptions can add critical insights to our understanding of the dimensions of these Davidic Psalms;.

If they are genuine, their words emerge out of flesh-and-blood reality. They are not simply abstract theological poetry; they are Scriptural truths embodied in the life of the Psalmist. And he turns his experiences (be they of joy and praise, on the one hand, or chaos, confusion and betrayal, on the other) into corporate prayers for the people of God for all time.

As such, in the words of one commentator, they can even provide us

“an important key which unlocks a world of understanding in the Psalter and of the days of its composition.”

Though much, much more could be written on the debates of the historicity of the superscriptions, for the purposes of this and later writings, we will hold to this latter position of their historical veracity.

And with that final word of introduction, we now move into the word study.

(And if you are at all interested, in footnote form at the end of the text, we will give a brief overview of James Thirtle’s theory regarding how the superscriptions and subscriptions were incorporated into the Psalter. Very interesting. Possibly helpful.

Now to the word studies, which will include both the Hebrew words, miḏbār and anah, due to the intrinsic nature of their connection.

miḏbār (מִדְבָּר)

217 occurrences in the OT

(of which we will only examine the first seven instances in the book of Genesis).

Etymology and Dictionary Definition

From dabar, in the sense of driving. As such, it can be translated as ‘pasture’ (i.e. an open field, where cattle are driven); by implication, it can also mean a ‘desert’ or ‘wilderness.’

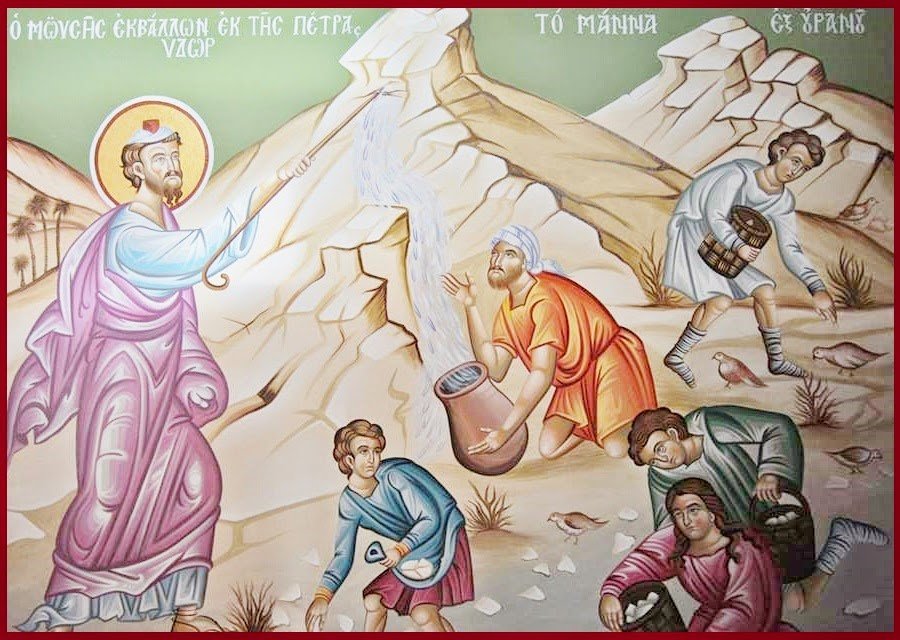

In the LXX, this Superscriptions is in Greek “en te ereme” (ἐν τῇ ἐρήμῳ), from which we derive the English term eremitic. In carrying this phrase into the NT, we can note the same phrase appears in the Gospels, which state that before Christ’s entrance into His ministry, the

“Holy Spirit drove Him (ekbállō) into the wilderness” (eis ten érēmon, Mk 1:12).

And a question we could ask from the life of David…then from the life of Christ is

Whether this pathway “into the wilderness” is a pattern for us who are called to follow in the footsteps of our Savior?

Summary Synthesis

The opening occurrence comes in the first war mentioned in Holy Scripture in reference to the pagan tribe of the Horites who live “in mount Seir…by the wilderness.” Their lands will ultimately be taken by Esau; yet before that the wilderness will come to be the dwelling place of Hagar and Ishmael (also an older brother, like Esau, whose inheritance passed over for the younger…).

Oppressed (anah) and driven into the wilderness by the very person that had ordered her to “go into” her husband, Hagar, now pregnant, confused, all alone, meets the Angel of the Lord “in the wilderness.”

A chapter before we had seen Abraham also alone and confused, struggling with the reality of God’s stated ‘Yes’ of a promised heir and the hardship of his experience of the ‘No.’ Yet, at the very same time, there JHWH also meets him. And as “a deep sleep fell upon Abram; and behold, horror and great darkness fell upon him,” he experiences the Covenant. Utterly helpless, he hears the word of a great and mysterious prophecy:

“Know certainly that your descendants will be strangers in a land that is not theirs, and will serve them, and they will afflict (anah) them four hundred years

This affliction of bondage will, nevertheless, begin to form within the collective consciousness of the people of God an archetype:

Suffering, however unjust and however long, is inextricably tied to the fulfillment of the Lord’s divine promise.

That is to say, we come to know the reality of this promise, paradoxically, through the hardship of our experience (which, we remember derives from the two Greek words, ex—’out of’ and peirazo—‘testing’; for, again, however paradoxically it sounds, we can come to know the reality of the promise out of the ex-perience of our affliction (anah).

To return back to Hagar, helpless, confused, all alone, she gives a name to JHWH:

You-Are-the-God-Who-Sees;

And while Ishmael, who will “dwell in the wilderness,” will not ultimately bear the yoke of His all-seeing, suffering Savior, we see that Abraham’s heir will. Joseph, a prefiguration of the Messiah, comes to know, understand, ex-perience, divine deliverance in the very bonds of affliction.

Yet his anah will open up, not only for himself, but moreover, for God’s people for all time the Covenantal blessing of life through

Christ our Passover

Who is sacrificed for us.

Detailed Analysis

The wilderness of pagan lands

In the first occurrence in Genesis, miḏbār refers to the “wilderness” of Mt. Seir. With the context being the “Battle of Kings”—the first war mentioned in Holy Scripture—the text specifies that it involved the “Horites in mount Seir unto El-paran, which is by the wilderness” (miḏbār, Gen 14:6) . So that we are aware, according to the ISBE, “the Hebrew Horite is the Khar of the Egyptian inscriptions, a name given to the whole of Southern Palestine and Edom as well as to the adjacent sea.” Further, as to mount Seir, it represented,

the alternative appellations [i.e. “mount Seir” and the “Land of Seir”] given to the mountainous tract which runs along the eastern side of the Arabah, occupied by the descendants of Esau, who succeeded the ancient Horites.

That is to say, the “Horites in mount Seir…by the wilderness” occupied a mountainous, desert region. And their pagan lands, as we find later in Genesis, will ultimately be taken by the warring tribes of Esau.

But next, as we see in the following occurrence, the “wilderness” will become a place of habitation for Hagar and her son, Ishmael. Linking the two together, then, one could comment that before Esau loses his inheritance and is passed over as the oldest son, Ishmael, the first and oldest son of Abraham loses the Promised Land for a wilderness.

An oppressed (anah) slave girl driven into the wilderness

The next four instances, then, speak of the pathway of Hagar out of the presence of Abraham and Sarai following the pregnancy and birth of Ishmael. With Sarai overruling her husband in contradistinction to the clear promises of JHWH (Gen 12:2, 13:14-17, etc.), she arranges for their slave to become his concubine, as it were, “securing” the promise through means of the flesh.

Yet, as soon as she had conceived, what do we find are the fruits of this carnal solution?

Immediately, problems begin (…which, we can say, have followed Israel even to the present day, from the Ancient Near East to the modern Middle East…). Hagar, we are told, begins to “despise” Sarai (qalal, a word often used in the OT to express the idea of “cursing” [Gen 8:21, 12:3, etc.]). Then Sarai responds by “mistreating/dealing harshly with” Hagar (anah, 16:4-6).

Now the works of the flesh are evident: sexual immorality…idolatry, withcraft (cf. I Sam 15:23), enmity, strife, jealousy, fits of anger, rivalries, dissensions, divisions, envy… (Gal 5:19-21).

A word on anah

The verb used here is anah, which is an important word in the Hebrew Scriptures, occuring 84x and comes to mean to “afflict,” “oppress” and “humble.”

This word, however, will be applied to the people of God in an extraordinarily paradoxical way in which affliction…leads to…flourishing (Ex 1:11-12). And, as such, it will be the exact means that JHWH Himself uses to “test” the “heart” of His people in their wilderness wanderings (Deut 8:2-3. of which more is said here), And such testing of the heart of God’s people through affliction, as we find in the remainder of the OT, will especially continue into their years of temporal stability and affluence in the Promised Land.

As such, we in the affluent West may be able to better see how God can use it in our own lives. For affliction is still promised to come to us, whether in physical bondage or, much more so, in relative wealth and ease…

In the words of David, when looking back over the trials of his life, from his wilderness exiles to his rise to power and 40 years of kingship, JHWH used anah in his life so that he can finally declare,

“Before I was afflicted (anah) I went astray,

But now I keep Your word” (Ps 119:67).

And even more,

“It is good for me that I have been afflicted (anah)”

And Why exactly?

“That I may learn Your statutes” (119:71)

Because,

“I know, O Lord, that Your judgments are right,

And that in faithfulness You have afflicted (anah) me” (119:75).

An incredible response.

Again,

“I [now] know [precisely because of my horrific trials of affliction that]

In faithfulness You—JHWH, my LORD God—have afflicted me.”

It is not just some other fallen, vindictive person that has done this to us (though it may, of course, involve their machinations).

On a primary level, it is, according to the Psalmist, the Lord Himself Who has afflicted us.

And David comes to understand that this is

“right.”

For it draws him—and us—to experientially

“learn [His] statutes.”

The first use: JHWH’s Covenant with Abraham

The first usage in the OT comes in the previous chapter of Genesis when Abraham, in the affliction of childlessness (Gen 15:2-3), questions JHWH as to how he could become a

“great nation”

in whom

“all the families of the earth shall be blessed” (Gen 12:1-3)

when he, at that point, still has

“no offspring” (15:3).

For, as we well know, Abraham asked his question not a few days or months after the promise…but a full ten years after the Lord first gave it.

And we should probably ask ourselves whether we would we do any better, who struggle to continue in prayer for a matter of hours or days? And we who, failing to continue in persevering prayer, then take the “broad and easy path” of self-resignation in some sort of reactive view of God’s providential ‘No’ to us…when, in fact, it was God Himself Who first gave us the proimise in His Word…

All to say, Abraham is struggling between the reality of God’s stated ‘Yes’ and the hardship of his experience of the ‘No.’

A promise with a strange prophecy about his descendents

The Lord, however, meets Abraham in this tension, responding to him in two ways that are both, we might say, very “physical.”

First, He physically brought Abraham

“outside and said,

‘Look now toward heaven, and count the stars if you are able to number them.’”

And Why does God do this?

“And He said to him,

‘So shall your descendants be’” (Gen 15:5).

Just as the stars which he can now see with his own eyes, “so shall his descendants be.”

Next, when Abraham “believes” and it is “accounted it to him for righteousness” (15:6), only then does JHWH reveal to him the reality of the everlasting Covenant with Abraham and his seed:

“I am the Lord, who brought you out of Ur of the Chaldeans,

to give you this land to inherit it” (15:7)

God brings him out from pagan lands that he may receive more from a greater, divine fullness.

Yet, again, Abraham, not yet receiving the promise, asks

“Lord God, how shall I know that I will inherit it?”

Then—and only then—does the second physical action occur, whose meaning will extend take two thousand years to be finally revealed:

“So He said to him,

‘Bring Me a three-year-old heifer, a three-year-old female goat, a three-year-old ram, a turtledove, and a young pigeon’” (15:8-9)

The ceremony begins.

“Then he brought all these to Him and cut them in two, down the middle, and placed each piece opposite the other” (15:10a).

In the midst of this ceremony, what follows is an overwhelmingly important prophecy that will mark Israel for all time.

Which is this:

To know, to understand the Covenant, God’s people must first experience the affliction (anah) of bondage and slavery.

The prophecy of Israel’s future affliction (anah)

The narrative continues as the sun goes down and a

“deep sleep fell upon Abram;

and behold, horror and great darkness fell upon him” (15:12).

Then, utterly helpless amidst the great darkness of this horror, Abraham hears this three three-fold prophecy of what his heirs must endure:

“Then He said to Abram:

‘Know certainly

that your descendants will be strangers in a land that is not theirs,

and will serve them (in the bondage of slavery),

and they will afflict (anah) them four hundred years’” (15:13).

That is to say, Abraham will become the “father” of a nation…which would be birthed through the centuries-long pangs of affliction.

Affliction, oppression, bondage…and Covenantal life…through the experience of a mystérion

In this initial use of anah we are opened up to a great mystery (mystérion in Greek; sacramentum in Latin).

As Abraham in the “horror and great darkness” of a “deep sleep”—where he has no power, no ability, to enact “do anything” himself—all that he, and all that we, can do is ‘shut our eyes and mouth to experience the mystery’ (mueó).

The mystery of suffering.

For “four hundred years” JHWH would allow His people to suffer.

This is to say, generation after generation after generation would be born into, and ultimately die in, bondage.

No vindication. No redemption.

(At least not on a temporal level.)

Yet, something is indeed happening.

In the course of time an archetype is being built within the collective consciousness of the people of God:

Suffering, however unjust and however long, is inextricably tied to the fulfillment of the Lord’s divine promise.

We come to know the reality of this promise—paradoxically—through the hardship of our experience (which, we remember derives from the two Greek words, ex—’out of’ and peirazo—‘testing’ [see the five-part word study on this concept); for, however insane it sounds to our 21st century Modern Western ears, we can come to know the reality of the promise only out of the ex-perience of our affliction.

The mystérion of the Incarnation…and Passion

Yet, we can go even one step further.

In our experience of this mystery of suffering, our inner person is being opened up to the very suffering of the Messiah Himself:

He is despised and rejected by men,

A Man of sorrows and acquainted with grief…

Surely He has borne our griefs

And carried our sorrows…

But He was pierced for our transgressions,

He was crushed for our iniquities;

The chastisement for our peace was upon Him,

And by His stripes we are healed (Is 53:3a, 4a, 5).

The Messiah, this Suffering Servant Who would bear the grief of His people, would ultimately become for His suffering people in their brutal affliction and slavery in Egypt…the very Passover meal itself:

For even Christ our Passover is sacrificed for us:

Therefore let us keep the feast (I Cor 5:7a-8b).

Returning to Hagar: In the affliction, the Lord’s presence

Hagar, suffering, afflicted, with no home, now pregnant and all alone, flees from her earthly masters.

And yet to her the Lord Himself comes:

“And the angel of the Lord found her by a fountain of water in the wilderness” (miḏbār, Gen 16:7).

“Found…in the wilderness.”

Is this many times where God finds us?

As Christ Himself was driven “into the wilderness,” are we sometimes led here too?

And here, do we, likewise, suffer the afflictions of being separated, being in need, being cast out by the very people that are given to care for us?

The text continues.

“The Angel of the Lord said to her,

‘Return to your mistress, and submit (anah) yourself under her hand’” (16:9).

That is to say, keep doing what you’re supposed to do; even if that means entering back into the affliction.

Then the Lord follows with an extraordinary (and, we might say, unexpected) promise:

“I will multiply your descendants exceedingly,

so that they shall not be counted for multitude” (16:10).

After then revealing to Hagar that this promise is already being fulfilled in her own affliction, God declares the name that she is to give to her son:

“Behold, you are with child,

And you shall bear a son.

You shall call his name Ishmael,

Because the Lord has heard (shāma) your cry of distress” (oniy,16:11).

When the Lord then prophesies of Ishmael’s pathway in life as a “wild man” whose “hand shall be against every man, And every man’s hand against him” (16:12), the narrative concludes with this word from Hagar.

Receiving the name of her son who is to be born, she then gives a name to God:

“Then she called the name of the Lord who spoke to her,

You-Are-the-God-Who-Sees;

For she said,

‘Have I also here seen Him who sees me?’” (15:13)

And with that, we will draw this study to a close. We will pass over how it was that her son, Ishmael’s life would be inextricably tied to the “wilderness” (The next two uses of miḏbār in Gen 20:20-21); though not, as we would find, in a redemptive, Covenantal way (cf. Gal 4:21-31).

Nor will we mention the story of the patriarch Joseph, who was ironically delivered from death by his older brother, Ruben, when the remaining ten sought to kill him (37:18-21), only to be “cast into this pit that is in the wilderness” (miḏbār, 37:22). There noting that is in a “pit“ (bôr) that was “in the wilderness”…which later becomes an actual “dungeon” in Egypt (40:15; 41:14), where Joseph, a prefiguration of Christ, learns the statutes of JHWH.

And, bearing the yoke of the Messiah, Joseph not only is brought out of bondage himself, but moreover, becomes the person through whom his people would ultimately be delivered in the future Messiah.

Amen.

So may it be!