The Rich Young Ruler, Part I: An Introduction to “The Paradox of Suffering” in Seeking Riches (Ktēma & Chrēma) vs Treasure (Thēsaurós)

[Reading Time: 9 minutes]

Introduction: The questions at the close

We closed the last writing on the transition from the Parable of the Rich Man & Lazarus to Christ’s encounter with the Rich Young Ruler with two questions:

If we in a moment lost everything, would we be blessing God in His wise providence or crying out in pain and agony?

In short, would we respond like the Rich Man or like Job?

To these, we should add a third:

When the answer to our prayer is that our circumstances don’t actually improve but, in fact, only intensify with our body being broken down still further and our religious friends coming to us, not to support us in the pain of our loss, but to confidently lecture and even accuse us for suffering them…how would we then respond?

What would we do with our pain?

Or to say it a different way, Where would we put our pain? Or even more precisely, on whom would we place our pain?

Would we seek to bear this bitter agony and pain ourselves or would we “in bitterness of soul” with tears of “anguish”, know with Hannah and later with David how to “cast our bitter lot (yᵉhâb) upon the Lord”?

The answer, we will find, depends on the deeper question,

What is it that we treasure (thēsaurízō)?

What is it that we are truly seeking in this life? Deeply desiring? Struggling after? What is it that is consuming our time and mental energy? Day in and day out; Night after night?

Our answer will be revealed, not necessarily in our words (were it that easy!) but in our actions, in the “lived concrete” of our lives, to use a term from Martin Buber; or in the language of Charles Taylor, our “lived belief.”

Treasure (Thēsaurós), Riches (Ktēma & Chrēma) and Suffering

The simple thesis will be that if we treasure those things that we can lose, then the satisfaction we derive from them is assured to be temporary…and the suffering that results from them…eternal. This transient form of treasure is conveyed by the New Testamental term “riches” (ktēma and chrēma) whose roots points to what we work to “acquire, posses” (ktáomai) and “use” (chráomai).

If, however, we treasure those things that we cannot lose, then our suffering is assured to be temporary—“but for a moment”—and our satisfaction and enjoyment of them eternal. The Scriptural term employed to express this reality of eternal treasure is thésauros.

Yet, as we move into a study of these terms, we find that in our seeking of either momentary worldly “riches” or eternal “treasure”, we will be guided either by the false holy spirit of This Age or the eternal Person of the Holy Spirit. As noted in our prior study on the Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus,

For “those who are rich” and, more to the point. for those who “trust in riches” (Mk 10:24, I Tim 6:17), their wealth becomes, as it were, the Holy Spirit for them.

It comes to their side as their Advocate when they are faced with uncertainty, whispering false securities. In present hardships, suffering, calamity, it extends a false hand of salvation.

When locked in patterns of sin, it surrounds them, shielding them (temporarily) from its consequences so they can continue to “feast sumptuously” in their (temporary) life in this (temporary) world.

Yet, these riches and the “consolation” that goes along with them do not last.

Will you set your eyes on that which is not?

For riches certainly make themselves wings;

They fly away like an eagle toward heaven (Prov 23:4).

And it the end, therefore, when we “return naked” to the grave as at our birth, we find that

Riches do not profit in the day of wrath,

But righteousness delivers from death (Prov 11:4).

The Paradox of Modern Suffering

These realities have been well summarized by research into what has been termed The Paradox of Modern Suffering, where our cultural pursuits of “higher levels of happiness and a lower level of suffering” has successfully produced a society that in numerous metrics is extremely prosperous (a word we will study in upcoming writings); yet at the very same time, has resulted in a populous that is marked by “existential suffering and mental distress.” In their words,

Since the end of the 18th century, many people in the developed Western countries have experienced an increase in housing conditions, income, security, health, and education levels as well as a progress in human rights and democratic values and institutions. These trends are often perceived as signs of a positive development towards a higher level of happiness and a lower level of suffering (Harris, 2008: 2; Hundevadt, 2004: 12; Milsted, 2007: 25).

Nevertheless, commentators like therapist Russ Harris and social anthropologist Thomas Hylland Eriksen have pointed out how several studies and surveys seem to indicate that the levels of existential suffering and mental distress have not decreased in line with this political, economic, and social development (Har-ris, 2008: 3; Eriksen, 2008: 7). Focusing on the growing standard of living, economist Richard Layard likewise remarks how people in the modern Western world experience existential suffering despite the ambition to create a happy society:

There is a paradox at the heart of our lives. Most people want more income and strive for it. Yet, as Western societies have got richer, their people have become no happier. (Layard, 2006: 1).

The article introduces the thesis of the paradox of suffering in modern Western culture. The concept of this paradox designates how modern Western culture is centred on a pursuit of happiness and avoidance of suffering, but continuously involves widespread existential suffering and mental distress. Furthermore, the main point of the article is to demonstrate how the cultural pursuit of happiness, paradoxically, is what causes a lot of the present suffering.

Against this back drop we have the wisdom of the Old and New Testaments.

Treasuring up true treasure

This “paradox of modern suffering” is elucidated in the Old Testamental, Wisdom Literature which is perfectly summarized in the simple words of Jesus at the center of the Sermon on the Mount:

Do not treasure up (thēsaurízō) for yourselves treasures (thésauros) on earth, where moth and rust destroy and where thieves break in and steal;

But (thēsaurízō) for yourselves treasures (thésauros) in heaven, where neither moth nor rust destroys and where thieves do not break in and steal.

For where your treasure (thésauros) is, there your heart will be also (Mt 6:19-21).

For anguish and suffering (derived from the Latin word, sufferre, ‘to bear, undergo, endure’ (which is further related to the parallel Greek word, hypomonḗ) is experienced, according to dimensions of research, when we “endure” what is “undesired” for a “considerable duration” and of a “considerable intensity.” It occurs when we undergo the “subjective experience of the loss of some perceived good” (Salvifici Doloris, 1984).

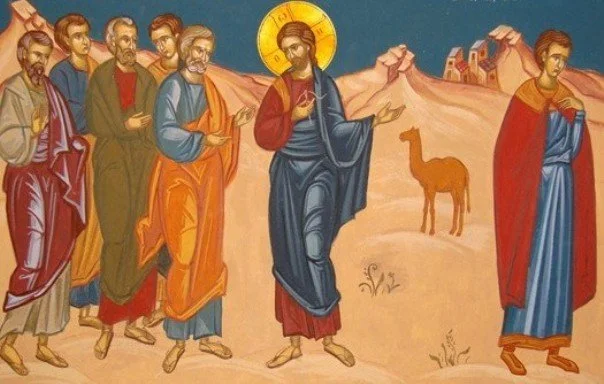

For the Rich Young Ruler, even with all of his moral virtue and theological understanding, the loss of the “perceived good” of his material riches was still too great for him to endure. Through his temporary possessions, he did, on the surface, experience “higher levels of happiness and a lower level of suffering”; yet underneath he had to deal with roots of growing “existential suffering and mental distress.”

Caught in the middle, he would finally turn away from Christ. And in that monumental moment which reveals to us where his true treasure lies, the text describes him with psychoanalytic precision as being perílypos.

That is to say, even the mere thought of such loss causes him to experience such an all-encompassing grief (lýpē) that encircles (perí) every bit of him so as to make him“exceeding sorrowful” ,“beyond measure, above strength.” And this grief, in short, is too much for him to endure such that

“He goes away grieving for he had great riches” (ktēma, Mt 19:22; Mk 10:22).

All the eternal riches of the divine Kingdom offered him by the One Who became incarnate as God literally with him, Who suffered and died for him in order that he may be in Him Who

“of God is made unto us wisdom and righteousness and sanctification and redemption” (I Cor 1:30).

Being, however, “exceedingly rich” (sphódra ploúsios), guided by the delusions offered him by the false holy spirit of This Age, he sees only the grief of temporary loss of what he could never keep, so that he loses the treasure that was offered him eternally.

Kyrie eleison!

And with these introductory words, we will delve into Christ’s encounter with the Rich Young Ruler in the upcoming writings, looking verse by verse more into the nature of riches (ktēma & chrēma), treasure (thēsaurós) and the paradox of suffering (perílypos).